In December, Tommy Battle’s dream came true. The five-term Mayor of Huntsville is Alabama to the bone, born in Birmingham and a graduate of the state university in Tuscaloosa, but for the past 18 years he’s tried to distance his city from the state’s unsavoury stereotypes.

Huntsville, in the north, is the home of the Saturn rocket program that took on the Soviet Union’s Sputnik. It houses the second-largest biotech research hub in the United States. And it has attracted high-end manufacturing investments such as Blue Origin’s rocket engine plant.

But Alabama tropes are hard to shake: The state is backward and full of bible thumpers and bigots – allegedly. When local companies try to hire from afar, Mayor Battle says recruits often hear the same responses when telling their spouses: “‘Huntsville?’ With one question mark. Then they say, ‘Alabama???’ With three question marks.”

Translation: You’ve got to be kidding me.

But in December, Huntsville had the last laugh. Eli Lilly and Co. was looking to build a US$6-billion manufacturing plant that would create 3,000 construction jobs and employ 450 engineers, scientists, lab technicians and operations staff. After narrowing down the field of 300 bidders, the pharmaceutical giant named Huntsville a winner, one of four new facilities in the U.S. It’s the state’s largest-ever private industrial investment, and it personifies the tagline the Mayor has preached: “Huntsville: a smart place.”

For eons, Canadians have viewed Alabama as a small state that, save for a few pockets, is dirt poor. All anybody seems to know about Alabama is that Montgomery and Birmingham were the centre of the civil rights movement. In 1963, when Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” he called Birmingham “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.”

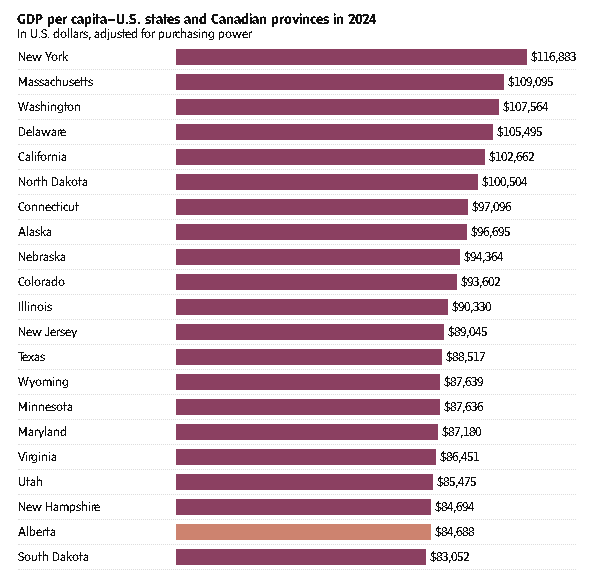

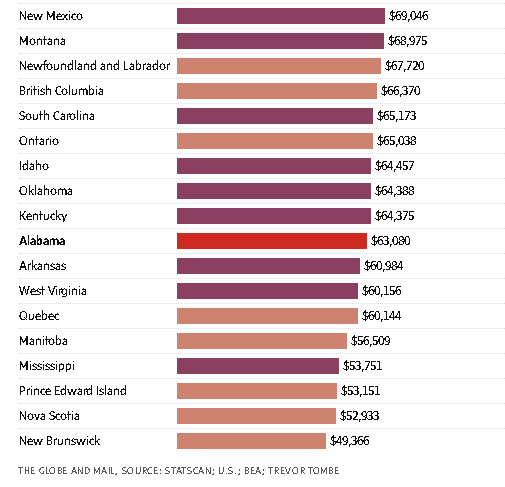

So, it was a shock when Canadian economist Trevor Tombe and the International Monetary Fund ran the numbers in 2023 and 2024 and concluded that Canada had, in fact, become poorer than Alabama.

To measure this, they calculated gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. In simple terms, it’s the size of the Canadian economy in a given year divided by the population. The same was done for Alabama. After adjusting for foreign exchange and some cost differences in both countries, the average for Canada’s 10 provinces was estimated at at US$55,000 in 2022, the same as Alabama. Shortly after, the IMF found Canada had actually fallen behind the southern state. (Canada has since edged ever-so-slightly higher than Alabama; the numbers are volatile from year to year.)

The timing was terrible for the Canadian psyche. Home prices were on an astronomical trajectory, inflation made everyday items such asgroceries far more expensive and there was deep resentment toward Ottawa. Canadians could probably stomach having their living standards slip relative to the broader U.S., the epicentre of the world’s tech revolution. But Alabama?

For an ego check, The Globe and Mail travelled to the Deep South to understand how this happened. Immediately, it was obvious Alabama is misunderstood. In Huntsville, there are as many Subaru Outbacks as there are pickup trucks, and the geography in Alabama’s two largest metropolitan areas – Birmingham and Huntsville – looks nothing like the historical imagery.

“Most people think of Alabama as flat pasture land with cotton fields,” says Daniel Hughes, a real estate executive who took his Montgomery-based company, BSR Real Estate Investment Trust, public on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Huntsville and Birmingham, though, are nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Looking out from Mayor Battle’s seventh-floor office in city hall, the landscape could easily be Vermont.

Alabama is also home to five million people – the same population as Alberta – and its economy is booming. The state’s unemployment rate is now just 2.7 per cent, versus 6.5 per cent in Canada, and its major employers include Airbus SE and giant defence contractor Northrop Grumman Corp. The state has also morphed into an auto manufacturing powerhouse with plants from Mercedes-Benz AG, Toyota Motor Corp., Hyundai Motor Co. and more. In 2024, Alabama made nearly as many vehicles as Ontario.

Of course, there is much more to an economy – and to quality of life – than industrial prowess. Alabama still has some serious flaws. For people living in poverty, there is almost no floor, and access to quality education remains a pipe dream for many.

There are also limits to how much can actually be gleaned from per capita GDP. It is not the Holy Grail. To start, one key variable is population, and Canada’s has exploded over the past four years. That alone skews the numbers.

But being on the ground in Alabama, it was obvious that Canadians need a wake-up call. They tend to view the economy through a historical lens – this is a G7 country that has long punched above its weight. Yet capital is global now and competition for it is fierce. If Canada isn’t careful, places such as the Deep South will continue to steal jobs. The Eli Lilly plant awarded in December could have just as easily gone to Montreal, a pharmaceutical hub.

In other words, it might be time to eat some humble pie. “People have a lot to learn from Alabama,” Mr. Hughes says.

Alabama’s sea change started in 1993. Historically, the state had an agricultural economy fuelled by slavery in the Black Belt, a stretch of rich, dark soil that was ideal for growing cotton. Over time, Alabamadiversified with forestry products, textile and apparel manufacturing, and steel – Birmingham had iron ore, coal and limestone, which are perfect ingredients. But eventually the mechanization of farming, foreign competition for steelmakers and a rising U.S. dollar became troublesome.

By the early 1980s, Alabamahad the second-highest unemployment rate in the country. At a 1985 seminar in Birmingham, Sheila Tschinkel, the director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, a central bankregional office, laid it all out. Companies, she said, were scared away by “the relatively low educational level of Alabama’s work force and its lack of flexibility, the state’s remoteness from national markets and deficiencies in infrastructure that make outsiders reluctant to move to many sections of the state.” It was a trifecta of doom.

Mercedes-Benz was the saviour. In the early 1990s, the automaker was struggling with high costs at its German plants and competition from Japanese luxury brands such as Lexus, so it decided to launch a luxury SUV plant in the U.S. The automaker made states bid against each other, and Alabama, North Carolina and South Carolina all ponied up big tax incentives. The cherry on top: All three are right-to-work states, which means unions can’t charge individuals mandatory dues.

In the end, Vance, a city just outside Birmingham, won the beauty contest. Sometimes it’s the little things that matter. Reports at the time said Alabama simply showed more zeal – plus the Germans liked the woods and rolling hills around Birmingham, which reminded them of the countryside around Stuttgart.

That single investment turned into the tip of a very long spear. A few years later, Honda Motor Co. Ltd. opened a plant in Lincoln, then Hyundai built its own near Montgomery. Mazda Motor Corp. and Toyota are now also in Huntsville, where they share a manufacturing facility. Auto suppliers have piled in, too. Michigan remains the top auto producer in Canada and the U.S., with two million vehiclesmanufactured in 2024, but Alabama is now in the top five, producing 1.2 million vehicles annually, close to the 1.3 million that Ontario churns out.

The irony of all this is that Alabama’s success was almost too good. The incentives started to strain the state’s finances.

Whenever a new opportunity emerged, Alabama would layer discounts on property and sales taxes as well as large capital investment tax credits on top of a competitive corporate tax rate. The state also wasn’t shy to layer on some cash grants. In other words, Alabama would throw the kitchen sink at new investments, and companies could use the benefits up front, before any revenue was generated.

ecause of this structure, Alabama often had to borrow money to fund the program. “We weren’t being great stewards to the taxpayers,” says Greg Canfield, the state’s former commerce secretary, who was tasked with fixing the problem. He has since developed something of a cult following in the state for revamping it while also keeping the investment dollars coming.

To fix the program, Mr. Canfield simplified it all, offering smaller tax credits for capital investments and adding in some time limits. Crucially, the incentives could only be accessed once companies built their facilities and hired employees, and there were clawbacks if companies didn’t keep their promises.

It was a risk, but Alabama didn’t feel as desperate anymore. “We felt like we could win most of the time based on having available sites, available work force, good business climate, low taxes and speed to market,” Mr. Canfield explains from the office of Burr & Forman LLP in Birmingham, where he is now a managing director of economic development. The last point was key. When companies invested in Alabama, they could receive permits and begin construction quickly. Red tape was for suckers.

Another signature achievement of his: putting together a marketing campaign for the state. “Whenever I had travelled around the world, nobody knew where Alabama was,” he says. “If they’d heard of it, it wasn’t a positive image.” He hired a branding agency and launched a campaign called “Made in Alabama.” Reminiscing, he pulls up the old slide deck on his iPad, grinning like a proud father.

At the local level, Huntsville deployed a similar approach. When Mayor Battle won his first election, in 2008, “we had great entry-level jobs. Hospitality, landscaping, etc.,” he says. “And we had great jobs on the top end, which was, you know, your rocket scientist, your technical person, your doctorate people who worked out at Redstone Arsenal. That middle ground was where our work force was lacking.”

Huntsville targeted its incentives toward this sector. Its first big win, in 2014, was a new plant for Remington Outdoor Co., the rifle maker. (Some stereotypes don’t die.) Soon afterward, Polaris Inc. arrived, opening a plant to produce its auto-cycle, the Slingshot, and an off-road utility vehicle, the Ranger. Then GE Aviation arrived, and then after that, Aerojet Rocketdyne, which now produces solid rocket motors in Huntsville.

The city also leaned into its expertise. After the Second World War, the U.S. government brought over German engineers who’d developed aircraft, rockets and missiles for the Nazis. This group eventually settled in Huntsville and worked out of Redstone Arsenal. (Despite their pasts, the U.S. decided it was more important to win the budding Cold War with the Soviets.) The scientists, led by Wernher von Braun, went on to develop the Saturn rockets used for America’s missions to the moon. It’s why Huntsville is now known as Rocket City.

All this innovation seeped into the city’s mindset. In 2004, two benefactors, the late Lonnie McMillian, a telecommunications executive, and Jim Hudson, a businessman who’d founded Research Genetics, a company that helped map the human genome, used their money to seed a life sciences ecosystem. To lead it, they hired the former director of Stanford University’s Human Genome Center.

The guiding hope was that one day the campus would attract world-class organizations. HudsonAlpha is now home to 40 biotech companies, and its home run came in December, when Eli Lilly came to town.

Robert Sbrissa has seen the boom up close. Originally from Montreal, he and his wife, Monica, moved to Birmingham in 1996 with two young kids. The financial software company he worked for was based in the U.S., and it asked him to move down. The family mulled it over, then bit. “It was a day in March that snowed about 15 inches in Montreal and I said, ‘Let’s give it a shot.’” The couple assumed they’d do a two-year stint. This August, it’ll be 30 years in Alabama.

Over dinner at the golf and country club in Greystone, the affluent neighbourhood where his family now lives, Mr. Sbrissa says their experience is a common one. “You get people who move here for work … and not a lot of people leave.“

First, the U.S. simply pays more for many senior white-collar jobs, and top personal tax rates in Alabama can be around 40 per cent. Today, they’re 53.5 per cent in Ontario. The size of the U.S. economy is also breathtaking – and companies make decisions faster. It’s a dream for someone in sales.“The entrepreneurial spirit was like nothing I had seen or experienced before,” he says.

Daily life was also a joy. Neighbours really are friendly in the South; the kids went to public schools equivalent to top private schools in Canada; and because the family could afford it, the health care is fantastic. Mr. Sbrissa recently got a magnetic resonance imaging scan within days.

As for Birmingham itself, there’s the beauty of the rolling hills, which deliver stunning fall foliage. And the city’s becoming a foodie hub. A new restaurant, Bayonet, was named one of America’s 50 best restaurants by The New York Times last fall. And despite the bible thumping, Birmingham has a sizable LGBTQ+ community and scored the same as Boston on the Human Rights Campaign’s Municipal Equality Index.

There is a “but.” The metro area, Mr. Sbrissa says, has noticeable income divisions. The public high school his son went to had a football field that installed the same turf as Gillette Stadium, the home of the New England Patriots. “You go 25 miles down the road and these kids don’t have books,” he says.

The way schools are funded is part of the problem. A good chunk of the money comes from town property taxes, In Greystone, the average list price for a home is currently US$1.5-million. In Woodlawn, which is close to the downtown core, it’s US$230,000. Alabama also has low property tax rates that average just 0.4 per cent annually, the second-lowest in the country. When they are multiplied by house prices, poorer areas have much less money to pay for quality teachers. It’s baked-in inequality that exists across much of the U.S.

Structural issues such as these leave a long tail of destruction, something Mashonda Taylor, chief executive officer of a community organization called Woodlawn United, is trying to combat.Woodlawn used to be a thriving middle-class community, but people fled after the Civil Rights Era and after the steel business in town petered out.

To rebuild, Woodlawn is using a multiprongedapproach: adding mixed-income housing; emphasizing public safety and green spaces; beefing up education opportunities, such as a subsidized early learning centre; and helping residents land stable, well-paying jobs. But the dire state of the community’s schools makes a rebirth that much more complicated. She sees residents in their 20s who struggle to break the cycle of poverty. “They didn’t learn how to read. Or do basic math,” she says. “So, you can’t get a higher-quality job.”

It’s often even worse in rural areas, which make up 42 per cent of the state’s population. Within the Appalachian Region, 26 per cent of adults read below third-grade level, and 40 per cent of adults struggle to solve math problems that require more than one step, according to the Appalachian Learning Initiative.

As for health care, in 2025 the Commonwealth Fund, a foundation that conducts independent research, ranked Alabama 42nd out of the 50 states for its overall health system performance. In rural areas, hospitals are having trouble simply staying open.

There are many ways to slice and dice the data to show how Alabama is far behind Canada when it comes to overall health, but one statistic sums it up. For all the investment dollars that Alabama has brought in, the state’s life expectancy is still just 74 years, the fourth-lowest in the U.S. In Canada, it’s 82 years, one of the highest worldwide.

All these nuances – the income disparity, the life expectancy, the kids who can’t read – epitomize why Jim Stanford, a veteran economist, is so mystified by the recent obsession with per capita GDP. The metric, he says, doesn’t capture what the average person receives from a country’s production.

He breaks down the formula to explain his point. There are multiple ways to calculate GDP, but he likes to use the income approach, which adds up everything earned in the economy – wages, profits and investment income. Mr. Stanford says only about half of GDP is paid to workers; much of the rest comes from corporate profits and investment income, and they mostly flow to the wealthy as shareholders.

To his mind, Ireland illustrates this problem best. By the IMF’s calculations, Ireland has the third-highest per capita GDP in the world, around US$150,000. Mr. Stanford says that is divorced from reality. “I’ve slung a Guinness or two in an Irish pub. Great country. Friendly people. Not rich,” he says. Ireland’s figure is skewed because many global companies book their international profits there, owing to the country’s low corporate tax rate.

As for the second component in the GDP per capita calculation – population – Canada’s soared by two million people in 2023 and 2024. That’s much faster than the equivalent U.S. growth rate on a percentage basis. It takes time for all these newcomers to start materially boosting GDP and offset their drag on the per capita number.

What, then, are Canadians to make of all this?

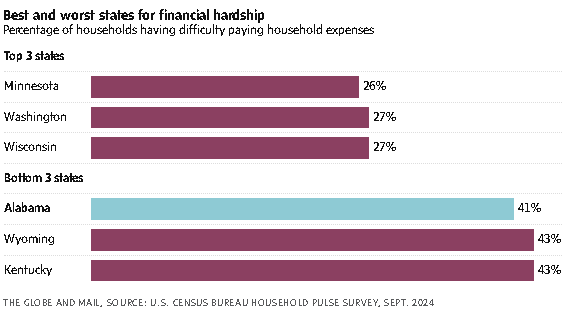

To start, per capita GDP isn’t the be-all and end-all. In Alabama, tens of billions of dollars of direct investment have poured in over the past decade, but the state’s minimum wage is still just US$7.25. Not every worker benefits. In fact, Alabama recently ranked as the third-worst state for financial hardship, according to official U.S. government data, with 41 per cent saying they had a somewhat difficult or very difficult time making ends meet.

Per capita GDP also doesn’t reflect social values. Canada has a high rate of unionization, which many people love. Meanwhile, Alabama has a total abortion ban except in dire health scenarios.

But there are things to learn from the South. Mr. Canfield, the former commerce secretary, can’t emphasize it enough: For businesses, speed to market matters. Companies that put capital at risk want to earn back those investment dollars as quickly as possible.

In Canada, Prime Minister Mark Carney has floated the possibility of a new pipeline from Alberta to the Pacific Ocean, but just this week, Enbridge Inc. said it won’t touch the project because it can’t sink more money into something that may never see the light of day.

Alabama’s evolution also poses a somewhat existential question for Canadians: In a competitive, global market, why should companies invest in the Great White North?

Last fall, there was an uproar in Ontario because Stellantis NV, the automaker, said it would shut a plant in Brampton, Ont. The timing, tied to U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff regime, dominated headlines. But what got lost is that Brampton, a suburb of Toronto, is now a very expensive place to live, with an average detached home price of $1.05-million. The union that representsStellantis workers has to fight for higher wages, and that makes the plant less profitable for the company.

Think about it from a CEO’s vantage point: If workers in Canada are more expensive, they should provide value over and above what a newly-trained – and cheaper – work force in Alabama can offer, especially considering there is now also an entire auto parts supplier network in Alabama and a major port nearby in Savannah, Ga., that’s bigger than any in Canada.

To Canada’s credit, it isn’t exactly standing still. One of Prime Minister Carney’s first moves last year was to establish a Major Projects Office to streamline regulatory reviews for projects that Ottawa deems to be in the national interest. Bye-bye red tape.

But the federal government can’t solve every problem. Over the years, there has been report after report on how to make Canada’s economy more vibrant. Boost interprovincial trade. Tap Canada’s highly educated work force to fuel the innovation sector. Recruit skilled immigrants. Canadians have the answers, and yet, somehow, nothing really changes.

Why is that? In 2007, one of these reports was commissioned by Stephen Harper’s government, and the authors, led by Red Wilson, came to this conclusion: “Canadians do not perceive that there is an imminent crisis.” Canadians certainly don’t want the country to fall behind as more nimble and aggressive competitors rise, the authors added, but they “do not appear to have a view about what needs to be done to avoid this outcome.” If Ottawa commissioned yet another report today, its conclusion could easily be the same.

So, yes, Canadians should take it all with a grain of salt. Alabama has its flaws. Per capita GDP does, too. But there is a glaring lesson in the Deep South: If Canadians remain complacent, the rest of the world will eat our lunch.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.