The Bank of Canada held its benchmark interest rate steady for the fifth consecutive time, in a tight-lipped decision that offered few hints about the timing of future rate cuts.

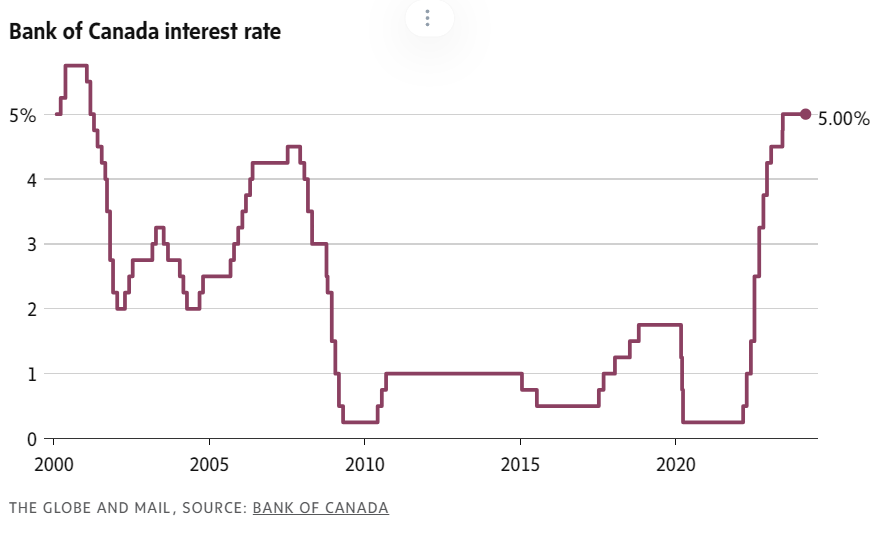

The widely anticipated move keeps the policy interest rate at 5 per cent, a level reached last July after one of the most aggressive monetary policy tightening campaigns in Canadian history, aimed at tackling runaway price increases.

With the rate of inflation inching closer to the bank’s 2-per-cent target, and the Canadian economy growing at a snail’s pace, central bank officials don’t expect to raise interest rates further.

At the same time, they’re not yet willing to entertain rate cuts, which would offer relief to homeowners with mortgages and businesses struggling to pay debts.

“With inflation still close to 3 per cent and underlying inflationary pressures persisting, the assessment of Governing Council is that we need to give higher rates more time to do their work,” Mr. Macklem said at a news conference after the announcement.

“We don’t want to keep monetary policy this restrictive for longer than we have to. But nor do we want to jeopardize the progress we’ve made in bringing inflation down,” he said.

In a highly unusual move, the bank left the entire last paragraph of its rate announcement unchanged from its previous statement in January, pushing back on private-sector speculation that the bank might use Wednesday’s rate decision to pivot to a more dovish stance.

Bay Street analysts and traders are betting the bank will begin cutting interest rates in the coming quarters. The key question is whether this will happen in April, June, July or perhaps even later.

Market reaction to the announcement was relatively muted, although investors pared back bets on an April rate cut. Interest rate swap markets, which capture market expectations about monetary policy, put the odds of an April rate cut at around 20 per cent, and the odds of a cut in June at just under 70 per cent.

“It wouldn’t be the Bank’s style to hint today about a rate cut as far off as June, so we’ll stick with our call for a rate cut that month despite the lack of fresh dovish talk today,” Avery Shenfeld, chief economist at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, said in a note to clients.

“Clearly, we’ll need more progress on inflation, and perhaps on wages, for that outcome, so we’ll be watching at the upcoming jobs and CPI data as we fine tune our forecasts.”

Mr. Macklem batted away questions during the news conference about the possible pace of interest rate cuts once the bank does start easing monetary policy. However, he did suggest that it could be a drawn out process.

“I think it’s very safe to say we’re not going to be lowering rates at the pace we raised them,” Mr. Macklem said.

The bank has made substantial progress in getting inflation under control. After hitting a peak of 8.1 per cent in the summer of 2022, the annual rate of consumer price index inflation came in at 2.9 per cent in January, back within the bank’s 1 per cent to 3 per cent target range.

Encouragingly, this decline has happened without the economy entering a recession or a major spike in unemployment. That increasingly looks like the “soft landing” many economists thought would be impossible a year ago.

The bank also noted that labour market pressures have been easing. That suggests that the rapid pace of wage growth seen over the past year could begin to slow – something the bank thinks is necessary to bring inflation back to its target.

Still, overall price pressures in the economy remain elevated. The bank’s preferred measures of core inflation, which strip out the most volatile parts of the CPI, are running in the 3 per cent to 3.5 per cent range. Mr. Macklem said he and his team need to see “sustained easing in core inflation” before considering rate cuts.

“One month doesn’t make a trend; you need to see a few months,” he said.

There are also pockets of the economy where prices continue to rise rapidly, putting pressure on household finances. Shelter price inflation, which includes mortgage interest costs, rent and other housing expenses, came in at 6.2 per cent in January.

Shelter inflation poses a particular problem for the central bank. Mortgage interest costs, which are directly tied to the bank’s own rate decisions, are the single biggest driver of CPI inflation. But if the bank cuts rates, offering relief to homeowners with mortgages, it would likely cause home prices to rise, further hitting housing affordability.

Likewise, Mr. Macklem has said the bank can do little to bring down rent inflation, which is being driven by a structural mismatch of housing supply and demand.

“Gasoline prices are expected to continue to add volatility to inflation in coming months, and shelter price pressures are likely to persist. In other words, the path back to our 2 per cent target will be slow, and progress is likely to be uneven,” Mr. Macklem said.

“Risks to global energy prices and transportation costs related to conflicts remain elevated. Domestically, inflation could prove more persistent than expected,” he added.

The bank expects CPI inflation to remain near 3 per cent until the middle of the year, then to decline to around 2.5 per cent by the end of the year and back to the 2-per-cent target in 2025.

The bank’s next rate announcement is on April 10, at which time the bank will also publish a new forecast for inflation and economic growth.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.