Canada’s fertilizer giants risk becoming the target of a U.S. price-fixing investigation as the Trump administration tries to tackle high input prices and low profits on American farms.

On Monday, Mr. Trump threatened to impose tariffs on Canadian fertilizer imports, while accusing foreign companies of anti-competitive behaviour and price fixing. The President has launched a Department of Justice probe examining the matter.

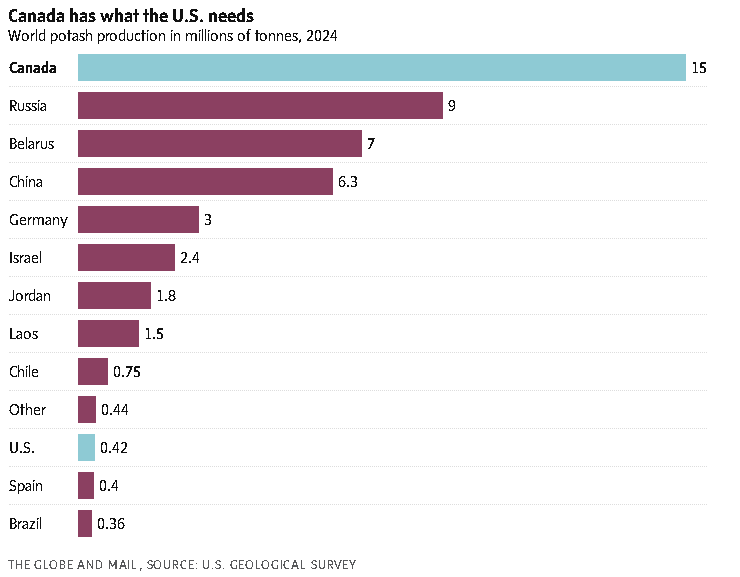

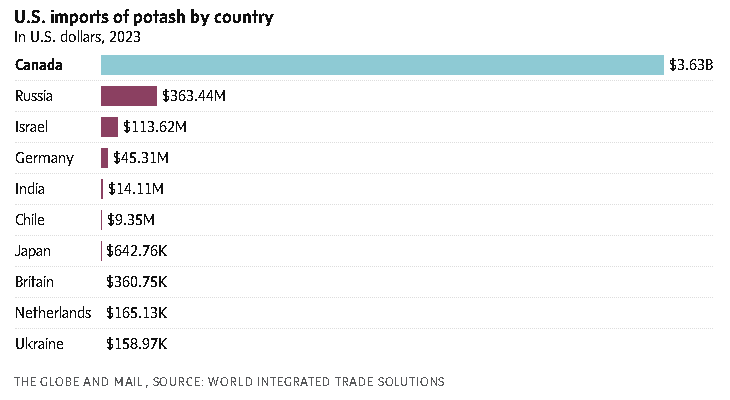

One Canadian company – Saskatchewan-based Nutrien Ltd. – is the largest global producer of potash. Potash is one of three fertilizers critical to all major agricultural operations and the U.S. depends on Canada for more than 80 per cent of its demand.

Mr. Trump’s accusations are misplaced, especially when it comes to potash, analysts and fertilizer industry associations say, but they tap into a real problem unfolding on the American farm.

U.S. eyes high tariffs on Canadian fertilizer, subsidies for farmers

Ottawa, Nutrien to meet to discuss building $1-billion potash export facility in Canada

On Monday, The White House announced US$12-billion in aid for farmers who have faced steep losses this year because of his administration’s trade policy. These funds are unlikely to cover the total costs. They also will not address the problem of farm input costs – the largest of which is fertilizer – outstripping farm revenue.

In 2025, China didn’t buy U.S. soybeans until late October, months into harvest. Soybeans are one of the U.S.’s top agricultural exports, and China has historically been its largest market. The market closed because of the Trump administration’s trade war with the Asian giant.

Despite sales resuming at the end of October, total soybean sales to all destinations through early November were 40 per cent lower than the same period a year earlier, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture.

The “Farmer Bridge Assistance Program” announced Monday is intended to help farmers market this year’s harvest and plan for next year’s crop. It has earmarked US$11-billion for row crop farmers.

But this won’t cover US$15-billion in nationwide losses accrued from trade war, and mounting input costs.

Fertilizer is one of the most costly inputs for a farm, accounting for more than 35 per cent of all operating costs for corn and wheat producers between 2006 and 2023. The three essential fertilizers are nitrogen, phosphate and potash.

The event that supercharged fertilizer prices was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, said Veronica Nigh, chief economist at the Fertilizer Institute. Russia is the largest fertilizer producer in the world.

In 2021, China also imposed export restrictions on phosphate and cut shipments by 40 per cent. China supplies around 40 per cent of global processed phosphate.

The costs have since come down from peaks in 2021 however have not fallen at the same rate as crop prices. Continued geopolitical instability has driven volatility. For example, Iran and Egypt are major exporters of urea (a nitrogen fertilizer), and conflict in the Middle East disrupted supply chains and forced prices high, Ms. Nigh said.

As a result of these low crop prices and high inputs, this year farmers across the U.S. are expected to lose on average US$150 per acre, with total nationwide losses eclipsing US$15-billion, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. The USDAalso expects these costs to stay at elevated levels going into 2026.

According to a statement from the American Soybean Association, this perfect storm of low crop prices, high production costs and loss of markets will lead to the longest stretch of substantial production losses for farmers of the crop in two decades.

While more competition would be a good thing in the fertilizer sector, which is consolidated, price fixing is unlikelyto be happening, said Josh Linville, vice-president of fertilizer at StoneX, a financial services company. Global commodity prices respond to global demand.

Mr. Trump’s focus on Canadian potash is also especially misplaced, he said. Nitrogen and phosphate prices are substantially higher. Potash has remained fairly stable over the past year. Supply is matching demand.

Sovereign fertilizer production would be good for farmers, Ms. Nigh said, noting the geopolitical instability of the past five years. Growth has stalled across thesector in the past three years, she said. This is largely because of permitting challenges.

But nitrogen and phosphate would be a better focus for growth than potash, Ms. Nigh said. In 2024, the U.S. produced 14,000 tonnes of nitrogen, 5,734 tonnes of phosphate and just 420 tonnes of potash.

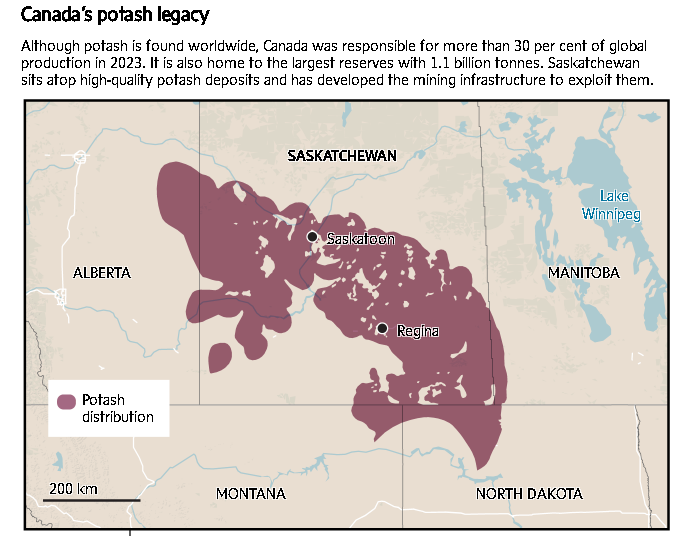

Potash production is tied to geography and geology. Potash is a rock mined from deposits thousands of metres under the ground. Very few places have abundant deposits. The U.S. has very little. Saskatchewan has the largest known reserves globally. And traditionally the U.S. and Canada have had very few trade disruptions, Mr. Linville said.

“We look at it as a North American market because, typically speaking, we get along quite well … a place where we truly need to place investment and increased production, it’s more on the phosphate side and nitrogen side.”

olicy volatility in the form of tariffs and trade wars is also unlikely to drive investment, Ms. Nigh said. Expanding or building new fertilizer plants costs billions of dollars and can take years.

Instead, the White House should follow the course charted over the past few months, she said. On Nov. 14, Mr. Trump issued an executive order to eliminate tariffs on imports of fertilizers.

These were good moves to bolster investment in fertilizer production, Ms. Nigh said, adding: Tariffs and accusations of price fixing are not.

“There is an underlying desire for some additional self-sufficiency or buffer,” Ms. Nigh said. “It’s about how we get there and we don’t want to cause harm to the domestic industry and to our important trade partners and to our growers.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.