A draft list of 32 major projects that could be candidates for fast-track approvals under the new Building Canada Act includes a pipeline that would bring Alberta oil through northwest British Columbia to the Pacific Coast.

Such a project is a priority for Alberta Premier Danielle Smith, but the B.C. government has questioned the practicality of a new oil pipeline and said it should not receive any public funding.

Ms. Smith has said she’s working with oil companies on a new pipeline proposal and that she’s confident she can convince B.C. Premier David Eby of the project’s merits.

The draft list, a government document obtained by The Globe and Mail, describes potential projects based on proposals Ottawa has received from premiers and other groups in recent months. It is not meant to be a final list, and it does not imply that any of the projects mentioned have been approved for inclusion, but it does provide a sense of the options on the government’s radar.

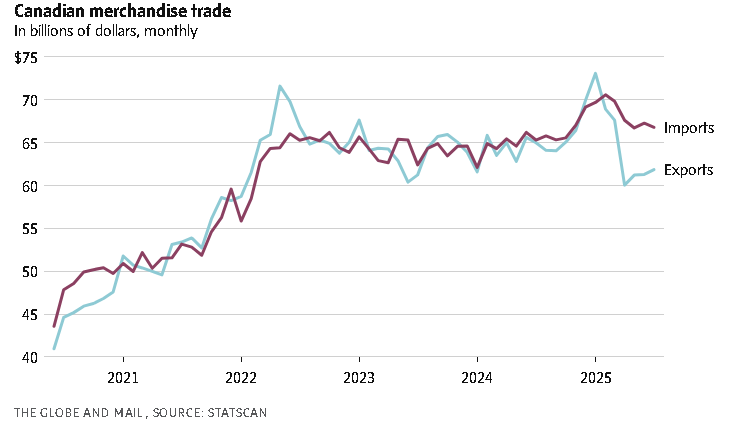

One of Prime Minister Mark Carney’s core campaign pledges in this year’s federal election was to identify and fast-track large projects as a way of spurring the Canadian economy, which is facing strong headwinds from U.S. President Donald Trump’s protectionist trade policies.

Mr. Carney and the country’s premiers have offered examples of projects that could qualify for federal support and potentially be expedited, but this list is the first to mention specific Canadian companies that would benefit and to group numerous options together.

Carney lays out federal criteria for fast-tracking infrastructure projects

Opinion: A nation-building project list alone won’t build a nation

Western premiers have been pushing for a Western trade and economic corridor, which is included on the list of 32 projects. The conversations have focused on road and energy infrastructure, with Ms. Smith saying she would like pipelines included.

The document describes the corridor project as being in the “concept” phase and says a Northwest Coast Oil Pipeline project “could be pursued within an economic corridor.”

The list describes the pipeline project as one that would link “Canadian heavy crude to markets in Asia.”

Coastal First Nations in B.C. have called on Ottawa to reject any new oil pipeline to the northwest coast.

Bill C-5, approved by Parliament in June, brought in the Building Canada Act. It allows the government to designate specific projects as being in the national interest, meaning they can then qualify for a faster approval process. Inclusion on the list does not necessarily mean the project would receive public funding from the federal government.

The process will be overseen by a new Major ProjectsOffice. The government recently announced that it will be based in Calgary and led by veteran energy executive Dawn Farrell. She is a former president and chief executive officer of Trans Mountain, who oversaw the completion of the pipeline project linking Alberta and the B.C. Coast.

The document was circulated within the department of Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. It is not clear who created the list.

What federal Bill C-5, the One Canadian Economy Act, is all about

The department referred questions about the document to the office of Dominic LeBlanc, the Minister responsible for Canada-U.S. Trade, Intergovernmental Affairs and One Canadian Economy. Mr. LeBlanc’s office provided a statement that did not comment directly on the document.

“Throughout the summer, Canada’s new government has been working with provinces, territories, industry, and Indigenous proponents to identify potential projects of national interest per the criteria of the Building Canada Act,” said Mr. LeBlanc’s spokesperson Gabriel Brunet. “In the coming weeks, the federal government will be announcing an initial set of projects that are under consideration for a national interest designation, or for a general referral to the Major Projects Office.”

Mr. Brunet said that before any final decisions are made, the Major Projects Office will undertake consultations with Indigenous peoples and other relevant parties.

“We are confident that the designated projects will help diversify our trading relationships and unlock Canada’s full economic potential,” he said.

The list in the document includes two projects that were recently mentioned by Mr. Carney, who said that an announcement on some major projects would be made within two weeks.

Ottawa to back port expansions as part of infrastructure push

Speaking in Berlin on Aug. 26, Mr. Carney said his government will make investment announcements related to building new infrastructure for ports, including those at Churchill, Man.; the Port of Montreal in Contrecoeur, Que.; and on the East Coast. He softened his language later in the day, saying it was a possibility that those projects could be among the first to be listed under C-5.

The list obtained by The Globe includes the Contrecoeur and Churchill port projects, as well as upgrades to the Port of Saint John and the Port of Belledune in New Brunswick.

The list of projects covers all provinces and territories. In addition to several port projects, it includes transportation projects such as roads, bridges, various mines and a range of energy projects, including oil and gas, nuclear, hydroelectric and offshore wind power projects and major new transmission lines. Some of the projects on the list are already in development. It also names specific companies that are behind various proposals.

Most projects on the list also include an estimate of the total cost of capital expenditures, or CAPEX, that would be involved.

The eight mining projects on the list include the Teck Strategic Minerals Initiative and the Red Chris Copper and Gold Mine expansion in B.C.; Saskatchewan’s Foran McIlvenna Bay and Rook Uranium projects; the Minago Nickel Project in Manitoba; the Crawford Nickel Project and the Ring of Fire in Ontario; and the Strange Lake Torngat Metals Ltd. rare earths mine in Quebec.

The 14 energy-related projects feature a heavy focus on Western Canada. The list includes a 750-kilometre transmission line linking Yukon and B.C. Other B.C. projects include LNG Canada Phase 2, which would expand the liquefied natural gas facility in Kitimat, B.C.; Ksi Lisims LNG, backed by the Nisga’a Nation; the North Coast Transmission Line that would help power critical-mineral mines; a dredging project at the Port of Vancouver that would accommodate fully loaded oil tankers in Burrard Inlet; and the Northwest Coast Oil Pipeline.

In Alberta, the list includes the Pathways Alliance proposal for a carbon capture and storage project.

Analysis: Carney tied carbon capture to new pipelines. Here’s how it could finally get built

The Taltson Hydro Expansion project in the Northwest Territories is on the list, as is the Iqaluit Hydroelectric Project for Nunavut.

A plan to build new small modular reactors at Ontario’s existing Darlington Nuclear Generating Station – recently estimated to cost $20.9-billion – is included.

Five other projects are in Eastern Canada, including the Gull Island Power Plant that is part of the Quebec-Newfoundland and Labrador new energy partnership; Newfoundland’s Bay du Nord offshore oil and gas project; transmission lines linking Prince Edward Island to the New Brunswick-Nova Scotia power grid; and proposed wind energy projects off the coast of Nova Scotia.

The five ports projects on the list also include the construction of a deep-water port and all-season roads linking Yellowknife to the Arctic Ocean, and a new Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project at the Port of Vancouver.

Speaking last week in Berlin, the Prime Minister said a “new port, effectively, in Churchill” would open up “enormous” liquefied natural gas and other opportunities. However, energy industry experts have questioned the merits of a Churchill port expansion, given the limited shipping seasons because of Arctic ice.

The document says the Port of Churchill expansion would be a multimodal rail and port trade corridor that could potentially include transmission lines to Nunavut and funding for icebreakers.

“With investments, the port has the potential to develop facilities for grain, minerals, potash, LNG and crude oil exports,” the document states.

Rounding out the list are five projects related to transportation. They include the Mackenzie Valley Highway project in NWT; various proposals to twin the Trans-Canada Highway; rehabbing the century-old New Westminster Rail Bridge in B.C.; the Alto High-Speed Rail project linking Toronto and Quebec City; and the proposed Western trade and economic corridor.